What is autism?

There is no one experience of autism.

The clearest definition is that autism – clinically referred to as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) – is a different way of thinking, a neurological developmental difference that changes the way you relate to the environment and people around you.

Put simply, autism changes the way that you see, experience and understand the world.

The world needs all types of minds.

What is the autism spectrum?

You might have heard people referring to autism as a ‘spectrum’. This is used to emphasize that there is an infinite number of ways that autism can be experienced.

While people on the autism spectrum share a range of similar characteristics, there are an equal number of differences between individuals, so the experience of autism varies greatly from person to person.

Dr Stephen Shore an autistic professor of special education at Adelphi University, New York, put it best when he said:

“If you have met one person with autism, you have met one person with autism.”

The support needs of autistic individuals can range vastly from person to person. Some individuals may want or need ongoing support in daily living, community participation, communication, while other individuals may desire little or no support in these or other areas.

While every individual has strengths and challenges, some of the key strengths identified in people on the autism spectrum at a higher rate than the general population include:

- being detail oriented;

- identifying irregularities;

- being a logical thinker;

- absorb and retain facts;

- tenacity and resilience;

- visual learners;

- in-depth knowledge in specific areas;

- honest, loyal and committed;

- maintaining a focus on a task; and

- seeing things from a different perspective.

It is important to remember that these are generalised strengths, and that many individuals on the autism spectrum do not have a strength in one or many of these areas and may in fact find some of these areas challenging.

My differences turned out also to include gifts that set me apart.

Many individuals on the autism spectrum can find enjoyment in routine and predictability, or engaging in a particular passion, activity or hobby. This can mean that people on the spectrum may be highly successful in their chosen careers or hobbies.

Just like there are some common strengths associated with the autism spectrum, there are a range of some common challenges that people on the autism spectrum may face. Some of these challenges can include:

- communicating wants, needs and desires;

- social interaction and interpreting other people’s behaviour or feeling that others do not understand their behaviours;

- processing sensory information; or

- processing cognitive information.

Individuals on the spectrum may develop skills in a way that is different from those that are not autistic. This can include the order in which skills are developed, the extent to which skills develop, and how skills develop. Skill development again, will vary significantly from individual to individual.

What are the characteristics of autism?

The characteristics of autism can vary widely in nature and presentation from person to person, and can also develop, change and improve over time.

Age, and cognitive ability can also influence how the characteristics of autism present themselves in different people, which is something that should also be considered.

While much of the diagnostic process is related to behavioural attributes, it can be difficult to diagnose autism until they are between 18-20 months. For some, the signs of autism may not become apparent until school years, or adult years when demands exceeds capacity.

Nevertheless, if you feel as though you, your child, or someone you love is on the autism spectrum, you may want to start the diagnostic process.

When I met people with autism, I realised how much I related to them, it made me realise that this is what it is like for everyone else all the time.

As autism is a varied spectrum of characteristics it can be difficult to identify if a person is autistic. To help you better understand the characteristics here is a summary of what to look out for, according to the latest diagnostic guidelines, the DSM-5.

Signs in developmental period

- In order to be diagnosed on the autism spectrum, characteristics must have been present in the early developmental period of a person’s life. It can be difficult to pick up on characteristics of autism for many parents, as raising a child in something that is very new to most people. For parents that already have a child diagnosed, they may be more aware of the early charateristics of autism so they pick up on these earlier.Or for other parents that have an older child that is not autistic, they also may pick up on the early characteristics of autism earlier as their children are developing differently. See our characteristics of autism in children checklist page for more information.

- For many adults, they many only become aware of the characteristics of autism in relation to their own behaviours later in life. When they then think back over their life they may start to identify how autism may have impacted their life at different moments such as realising that others seemed to know what others were thinking when they found it difficult to read people’s emotions. Many autistic adults have learnt strategies to support their challenges throughout their lifetime. It is therefore important to think about what characteristics were present at a young age when seeking a diagnosis as an adult. See our characteristics of autism in adults checklist page for more information.

To be diagnosed with an Autism Spectrum Disorder an individual does not need to have difficulties in all areas but rather must meet a specific combination of criteria across two domains. It is important to keep in mind that this is just a short summary, and that only trained, accredited professionals can make a formal autism diagnosis.

Domain A: Social communication and social interaction

Differences or challenges relating to language and social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts, both currently or historically. These include difficulty or differences in:

- Social-emotional communication and personal exchanges.

- Non-verbal communicative behaviours used for social interaction.

- Developing, maintaining and understanding relationships.

Domain B: Repetitive or restricted behaviour, interests or activities

Restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests or activities in at least two of the following:

- Repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech.

- Insistence on things being the same, inflexible and insistent on routine, or ritualised patterns of verbal or non-verbal behaviour.

- Engage in passions, activities or hobbies with a great focus and which can bring intense enjoyment; and

- Unexpected reactions, to sensory input, or an unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment.

Functional impact of autism on a person

For some people autism can impact all areas of life significantly, while for others it can impact certain aspects of life to a lesser degree. Because of this, autism is referred to as a “spectrum” and diagnosed based on both characteristics and the impact that these differences may have on a person’s life over time.

If the characteristics shown by a person are causing significant challenges in social, personal, family, occupational or other important areas of a person’s life then it is likely that the person will be diagnosed with an Autism Spectrum Disorder.

If the characteristics are not having a negative impact on a person’s life or relationships, and they are able to engage in all social and interpersonal settings, it’s unlikely that autism will be diagnosed.

The specific behaviours that capture the criteria listed above and the degree to which they affect daily life differ between individuals and can be influenced by factors such as age, learning and available supports. Due to this variability, the DSM5 provides severity levels 1 to 3 for each of the two domains to reflect the degree to which the behaviours they capture interfere in the individual’s daily life requiring support.

NOTE: It is important to remember that these severity levels are a snapshot of functioning at the time of diagnosis and may change over time as skills develop and/or demands change.

These three levels, and the characteristics and support needs that define them, are listed in the DSM-5 as:

- Level 1: “Requiring support”

- Level 2: “Requiring substantial support”

- Level 3: “Requiring very substantial support”

While Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder and Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) are no longer diagnosed as a separate disorder under the current diagnostic criteria (DSM-5), a person with a pre-existing diagnosis under the previous diagnostic criteria (DSM 4) can continue to use their pre-existing diagnosis.

What is Asperger’s syndrome?

In 1994 Asperger’s Syndrome appeared as a separate presentation of a pervasive developmental disorder in standard diagnostic manuals.

The key characteristics of Asperger syndrome identified at the time were:

- Difficulties with social interaction and social communication

- Restricted and repetitive behaviours

- No intellectual disability

- No delay in verbal speech development

In May 2013, the diagnostic criteria for autism changed with the release of the latest diagnostic manual (the DSM 5).

Since then “Autistic Disorder” and “Asperger’s syndrome” are no longer differentiated as separate presentation of pervasive developmental disorders, but are now included under the single diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) or referred to as autism.

Positive self-identity and self esteem

My autism is the reason I’m in college and successful. It’s the reason I’m good in math and science. It’s the reason I care.

People on the autism spectrum have strengths, skills and passions and often achieve great things, for themselves, their community and our world.

For some people a diagnosis of autism can enhance their self-identity and further develop their awareness of what makes them unique – autism becomes a positive part of their identity.

Many successful people in our community are autistic, some significant discoveries, developments and achievements have been made by autistic people, and without this neurodiversity in our society we certainly would not have achieved some of our greatest leaps in understanding about our culture, societies, communities and our world.

The neurodiversity movement

I am different, not less.

Neurodiversity was first coined in the mid-1900s by the Australian Sociologist, Judy Singer who recognised that “neurologically diverse (people) needed a movement of their own”, and that voicing “differences in neurology should be recognised and respected.”

The neurodiversity movement is a social and advocacy initiative that recognises and values this, based on the preference that neurological differences as natural variations in the human brain. Originating from the autistic rights movement, it now encompasses a range of neurological differences such as ADHD, dyslexia, and Tourette’s Syndrome. This movement is celebrated and important for several reasons.

The movement acknowledges neurological diversity as an essential and natural aspect of human diversity, similar to gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or disability. The movement challenges the traditional view that treats neurological differences as disorders or deficiencies, the movement promotes a more accepting approach which is why it is so celebrated.

The movement also advocates for inclusivity and acceptance in society, urging changes in education, employment, and social policies to cater to diverse neurological needs to benefit all.

The movement empowers neurodivergent individuals, encouraging self-determination and the right to advocate for oneself and highlights the unique strengths and abilities of neurodivergent individuals, instead of focusing solely on challenges and limitations.

With its introduction and gaining of momentum, the neurodiversity movement’s significance in Australia and globally lies in its ability to foster a more inclusive society that respects and supports all forms of human variation, enabling individuals with neurological differences to live respected and fulfilling lives.

What is the prevalence of autism?

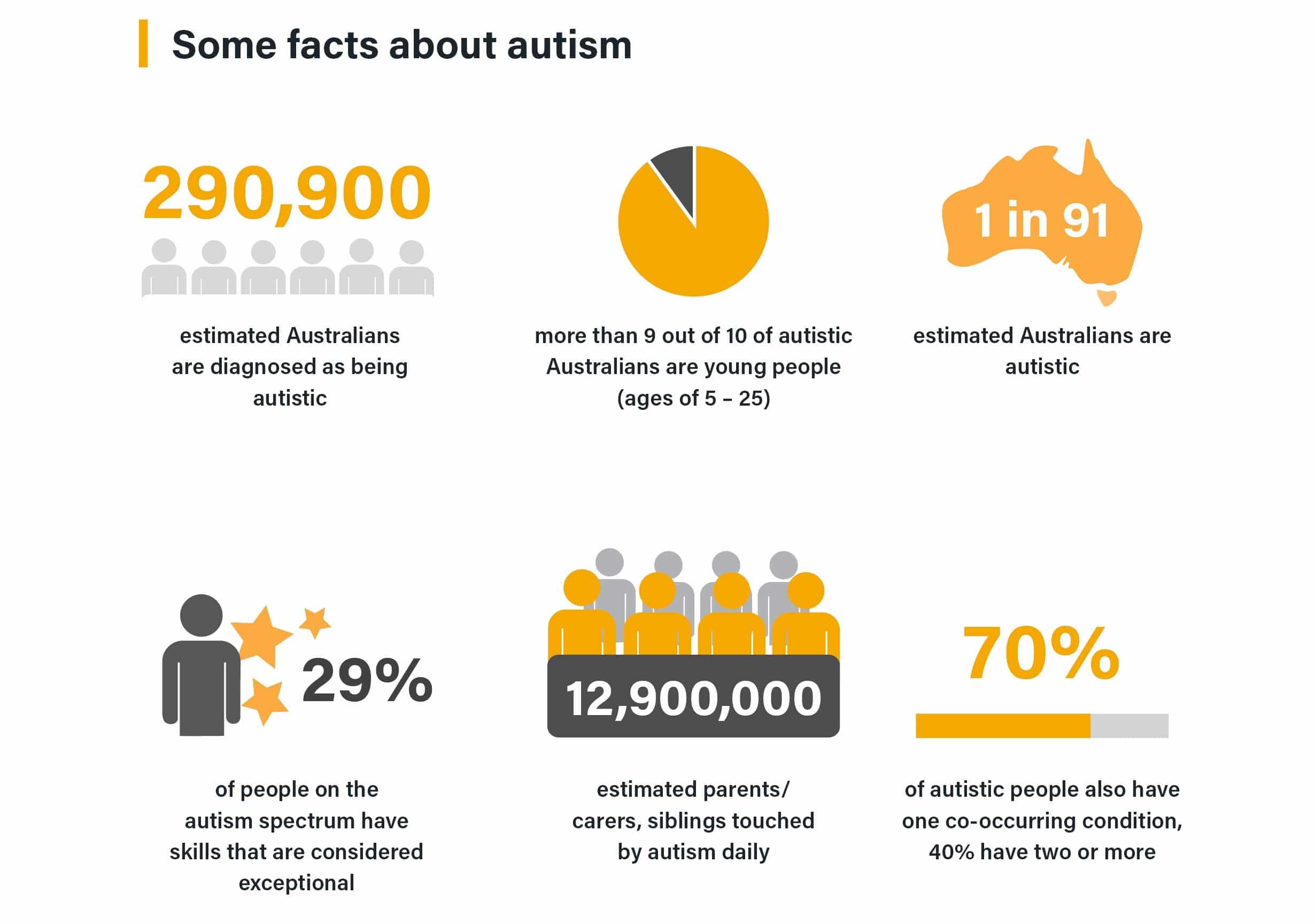

The exact prevalence of autism in Australia and internationally is unknown.

However, international prevalence research indicates that around 1% of the international population have an autism diagnosis of sorts. While some countries report higher rates, such as the USA (around 1:59), other countries report much lower prevalence rates.

Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2022 Disability, Aging and Carers, Australian: Summary of Findings shows that:

- the number of Australian diagnosed as autistic has increased over the past decade, from 164,00 in 2015, 205,200 in 2018 and 290,900 in 2022

- around nine out of ten people diagnosed as autistic are under the age of 25.

- 1 out of 2.2 Australian diagnosed as on the autism spectrum are female

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) is due to release more updated data on the autism prevalence in Australia in mid 2024.

While the reported prevalence of autism varies around the world, there has been a clear increase in the number of people diagnosed on the autism spectrum in recent years, but this doesn’t necessarily suggest that there are more autistic people in the world than there were ten or twenty years ago.

Evidence suggests that the increase is the result of a number of cultural and clinical factors, including social influences driving greater awareness of autism, and improved diagnostic procedures and changes in diagnostic criteria allowing more people to access a diagnosis.

According to Professor Whitehouse, from Australia’s Autism CRC, research shows the majority of the increase in autism prevalence over this period was due to an increase in diagnosing children with less complex behaviours.

“We now recognise that the condition presents along a spectrum. It is critical that we are all aware of the full range of presentations, as well as the considerable strengths that individuals on the spectrum bring to our community,” Professor Whitehouse said.

Autism in australia

Autism is a neurological difference, a different way of thinking. The word ‘spectrum’ reflects the diversity of autistic people and how characteristics present. There is not one single cause of autism. The following is an overview of autism in Australia at the time of publication.

Sources:

• Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022). Disability, Ageing, and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings. [https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/autism-australia-2022.]

• Australian Bureau of Statistics (2018). Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings [https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/disability/disability-ageing-and-carers-australia-summary-findings/latestrelease#

autism-in-australia]

• Australian Bureau of Statistics (2015). Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of

Findings, 2015 [https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Previousproducts/4430.0Main%20

Features762015?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=4430.0&issue=2015&num=&view=]

• Clark, T., Jung, J. Y., Roberts, J., Robinson, A., & Howlin, P. (2023). The identification of exceptional skills in school age autistic children: Prevalence, misconceptions and the alignment of informant perspectives. Journal of Applied

Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 36(5), 1034–1045. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.13113

• Whitehouse AJO, Evans K, Eapen V, Wray J. A national guideline for the assessment and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in Australia. Cooperative Research Centre for Living with Autism, Brisbane, 2018.

What is the history of autism?

The understanding of autism has developed over a number of decades. While the term ‘autism’ was defined by Kanner, there is varying evidence that other professionals, including Grunya Efimovna Sukhareva and Paul Bleuler, had recognised the unique presentation of characteristics much earlier than this. Since the 1940’s the diagnostic criteria has evolved and shifted as we learn more but now autism is widely understood as a spectrum of conditions with wide-ranging degrees of presentation.

1943

1944

A year later, Hans Asperger, a paediatrician at the University of Vienna in Austria wrote an article about children he had observed who shared similar characteristics of those in Kanner’s clinic but on a wider spectrum.

However, it has been suggested that Asperger and colleagues in Vienna had in fact been analysing and describing autism since the 1930s and that colleagues of Asperger actually played a key role in Kanner’s work in the 1940s.

Part of Asperger’s approach was to create a school that was centred around these children’s cognitive strengths rather than any perceived difficulties they faced.

What was notable was the diversity of the characteristics displayed by the children in Asperger’s clinic – an aspect of autism about which we have begun to have a greater understanding in recent years.

As Asperger’s research work was undertaken during the years in which Austria was under control of Nazis, his article was not translated into English for nearly forty years. So that, his findings did not become widely accessible until 1981.

1981

1989

1994

1996

2013

What causes autism?

Significant research is being conducted all over the world into the causes of autism, and while studies have suggested a number of possible associations and correlations, the causes of autism are still largely unknown.

While research into the causes of autism is continuously evolving, we do know that it’s likely there is not one single cause of autism, but rather autism is heterogeneous, meaning there are a number of causes for autism. Research also has shown that there is likely to be a number of contributing factors that lead to the neurological differences we recognise as autism or the autism spectrum.

Genetics

Researchers have found many possible genes that might play a role in the development of autism, leading to a belief that autism is in fact a number of different conditions that all have relatively similar behavioural signs and characteristics.

Research supports that for groups of autistic people, there are genetic differences across a range of genes or specific genes that cause neurological differences, which means that they display autistic characteristics.

Research into family genetics and the prevalence of autism has supported this finding. Research has shown that if there is one person in the family diagnosed as autistic, it can increase the likelihood that others in the family will also be on the autism spectrum, at the following rates:

- Aunts, uncles, cousins (2-3%)

- Siblings and non-identical twins (10%)

- Identical twins 80% if one is diagnosed

For some groups of autistic individuals, it appears that the genes are passed on from a parent directly, for others, genes from both parents are combined, meaning that they are likely to cause neurological differences resulting in autism, while for other individuals there may be genetic differences that have not been passed on, but have arisen during fetal development.

For a number of autistic people there are clear genetic variations that have shown to be the cause of their neurological difference, while for many other people diagnosed there appears to be no significant genetic differences.

Ultimately this means that while genetics seems to be the clear cause for some types of autism, either through de novo or genetic variations, at this stage they do not explain the cause of everyone’s autism.

Other possible contributing factors that are currently being researched because of their ability to influence neurological development include:

- Lower birth weight, and premature birth

- Advanced paternal age at time of conception

Research has identified that every individual on the autism spectrum has different neurology to each other, further supporting the notion that autism is a spectrum of conditions. While there have been a range of research studies into these areas, more research is needed.

There has been significant research into what does not cause autism. It is clear that autism is not caused by vaccines, bad parenting or the food we eat.

The facts about autism and common misconceptions

Are you finding that well-meaning family and friends, media commentators even some health professionals are making you more concerned and confused about your own or your child’s autism or suspected autism?

Misinformation and mixed messages can lead to feelings of guilt and isolation and can work against a proactive diagnosis and support program. Although the global understanding of autism is constantly evolving, here are some of the commonly understood facts, to help you put some of these misconceptions about autism to bed.

What are the causes of autism?

It’s natural to want to know what causes autism, however it is likely that there is not one single cause. While genetic differences are known to cause some types of autism, the causes of autism are largely unknown.

We do know that autism is a neurobiological difference, meaning that the brain processes information differently for autistic people, than it does for people who are not autistic.

We also know that parenting styles do not cause a child to develop autism.

Autism is not caused by vaccinations during or before pregnancy, and the falsely-reported link between the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) immunisation and autism has been retracted from the paper it was published in, and completely discredited by the research, scientific and medical community.

For more information about the current studies being undertaken into the causes of autism, visit our what causes autism section.

How is autism diagnosed?

Fortunately, the way autism is assessed has changed and improved over the last 80 years.

We now recognise a wider range of characteristics as forming part of the autism spectrum.

As awareness increases, parents and professionals are getting better at identifying early characteristics of autism and are more likely to seek an autism assessment.

This contributes to the explanation as to why people think autism is more prevalent today than it was ten or twenty years ago.

For more information about diagnosis go to our How to get an autism diagnosis page.

Do autistic people all look and act the same?

Autistic people are part of the diversity that is humanity, where no-one person is the same as another.

Research completed as far back as the 1940s revealed that autism is a spectrum of behaviours and skills.

For more information about the behaviours relating to autism, visit our signs and characteristics page.

Are autistic people physically or intellectually disabled?

Autistic people do not look different to other people and are usually physically healthy.

Autism is not an intellectual disability although some autistic people may also be diagnosed with an intellectual disability.

Do autistic people communicate?

Everyone communicates. Many autistic people communicate using speech. For some people the way speech sounds may be unique including using a mono tone, very formal language for the context in which it is used or use an accent. For others, verbal speech might be delayed or many not develop. It is important to develop ways that a person can communicate their needs to those around them.

I can remember the frustration of not being able to talk. I knew what I wanted to say but I could not get the words out, so I would just scream.

Some people use alternative communication systems such as sign language, picture exchange systems, or assistive technology to communicate with those around them.

Do autistic people have emotions?

Autistic people feel the same emotions as their parents, family or friends. People on the autism spectrum may express and feel emotions in a way that is different to people that are not autistic. They may have difficulties in expressing their emotions in a way that non-autistic people understand or recognise- this can cause frustration.

Some autistic people may shout or hit out when distressed but this is usually a reaction or last resort when there is a difficulty in communicating.

It is common for autistic people to have difficulty recognising and interpreting the emotions of others- know as alexithymia-, but many individuals develop strong bonds with important people in their lives such as parents and siblings like everyone else.

For some people, typical means of showing affection can be more difficult, such as maintaining eye gaze and physical contact.

For more information about the behaviours relating to autism, visit our signs and characteristics page.

Do autistic people make friends?

Most autistic people often do want to have friends, but have difficulty engaging socially with others or knowing how to recognise and respond to the intentions and emotions of others, particularly towards non-autistic people. This is known as the double empathy theory.

Understanding how people interact and engage with others is complex and is generally required to form friendships. Many autistic people report that they find this difficult to understand and navigate and often seek supports and services to support their ability to make and maintain relationships, including romantic relationships, relationships at work and social relationship. Planned activities around shared interests are often the key to supporting the development and maintenance of friendships.

For more information about the behaviours relating to autism, visit our signs and characteristics page.

Can autism be cured?

Autism can no more be “cured” than eye colour, pitch of voice, your height or the shape of your feet.

Early diagnosis and support can help individuals to develop skills necessary for a full, productive and satisfying life.

People who say they or their children were ‘cured’ may have been particularly successful in acquiring skills which enable them to become more effective through their everyday life.

Many people who have a diagnosis of autism are concerned about the concept of “curing” autism, as they feel it is their autism that makes them, them. Many people contribute their successes to being able to think in a totally different way then the vast majority of people that are developmentally typical.

This celebratory perception of autism led by people on the autism spectrum is called the neurodiversity movement.

Broaching the subject of autism

With an increased awareness of autism in our society you may start to recognise the characteristics of people you know or love as “on the spectrum” or “autistic”.

While it’s exciting that people are becoming more aware of the full spectrum of autism, it’s important for people to also be sensitive about the language they use surrounding it, and when approaching autistic people.

Before you raise the subject of autism with a person who may be autistic (or their families), it’s important to consider the following:

- Why do you believe it’s important to raise the subject with a person?

- What are the potential positive outcomes e.g. support and understanding, or improved self-awareness and identity?

- What are the potential negatives e.g. denial, confusion.

- You may need to be prepared to accept a negative response and to be supportive and non-judgemental.

- Who might be the best person to raise the subject – for instance it may be better coming from a family member or trusted friend.

- What tone will you use? Certainly, you will need to be respectful and sensitive.

- Avoid giving specific advice

- Find out about support services that might be helpful before having the conversation.

- Remember that you are NOT likely to be in a position to diagnose, unless you are trained to do so. You can raise the topic, and suggest the person or family member seeks more information on autism from a recognised and qualified professional.

To find out more information about the autism spectrum, see our signs and characteristics page.