Autism strategies and practices

Without deviation from the norm, progress is not possible.

Being autistic

How people experience the world varies widely from person to person, but there are some things in common between autistic individuals.

Generally, individuals experience sensory and cognitive processing differently than those not on the autism spectrum, and have differences in social interaction and interpreting other autistics is easier than interacting and communicating with non-autistic.

Some individuals are extremely passionate about a particular topic and like to talk or engage in it for extended periods of time, while others may have very limited language skills. Some autistic people might like loud noise and lots of movement, others might be highly sensitive to noise and don’t like to be touched. Some enjoy a consistent routine and don’t like it to change, while others are more flexible with routines.

As individuals process the world differently, they have unique insights and can often see things in ways others don’t.

The different perspectives and experiences of the autistic and neurodivergent community are vital to our society and it is important that autistic people are provided the opportunities for their voices to be heard and their differences celebrated. Being autistic also can come with its own set of challenges in experiencing and engaging in the world around them.

It is common for some autistic people to become anxious with changes to their routine or environment. This can make everyday tasks like leaving the house – even popping up to the shops – a difficult exercise.

Some individuals are highly sensitive to particular noises or touch, so being in public places or at social occasions can be overwhelming and upsetting.

Some individuals experience what is known as hypersensitivity – where the senses are heightened and everything is experienced intensely. The opposite of this is hyposensitivity – where the senses only respond to extremes. This can extend to not feeling any pain or only seeing the outlines of objects.

Some autistic people– particularly children – can experience extra complexities with understanding and managing their emotions. This can result in feeling overwhelmed and experiencing meltdowns.

What are the benefits of support and services?

Understanding how autism will impact on you, or your child’s life, allows you to access supports and services that can help manage challenges and build on strengths.

Once you have a diagnosis, it’s common to feel a bit overwhelmed about what to do next. The good news is there are many options for getting assistance. Due to there being so many options it can also be a little overwhelming and can take a while to get your head around what’s best for you, or your child.

Make sure you give yourself time to research what is available and what best suits your unique circumstances. Talk to your health professionals and don’t be afraid to ask questions until you’re satisfied you have the answers you need.

A diagnostic report will often provide information regarding strengths and challenges, which can help you develop a support plan – this is basically a plan that combines different therapies and types of supports and services specifically designed to meet you or your child’s needs.

Some areas that supports and services might focus on include daily living, social and community participation, health and wellbeing, lifelong learning, relationships, and choice and control.

While the term ‘intervention’ refers to taking action or using a technique to try to improve or develop skills in a particular area, there are varied terminologies for these developmental actions or activities.

Some common terms for supports and services include:

- Strategies

- Practices

- Programs

- Approaches

- Therapies

- Early interventions

Strategies and therapy approaches are generally individually designed to support a single skill or goal. Therapy strategies are used to develop the individual’s skills (using grading, prompt fading and task breakdowns), to adapt their environment to meet their needs or skill level (using visual supports, educating the child’s support people or incorporating environmental changes or the use of equipment), or often a combination of both.

Therapy programs and approaches generally consist of a set of evidence-based practices or principles implemented to achieve impactful learning for the individual’s and their support people for the individuals goals. For example, the Sequential Oral Sensory (SOS) Approach to Feeding intervention program.

Therapy and therapeutic intervention are generally practices or interventions that are provided by allied health professionals including: Speech Therapists, Occupational Therapists, Psychologists, Social Workers, Psychiatrists, and Art and Music Therapists.

Early intervention or Early support refers to therapy support specifically for children under seven years old, and can be put in place as soon as a diagnosis is made, or sometimes earlier when developmental differences are observed.

For more information about key evidence-based practices and strategies for people on the autism spectrum visit our Communication strategies, Behavioural strategies, Sensory strategies, and Social strategies pages in this section.

The value of early support

Children who are diagnosed as autistic at a very young age – that is, before the age of seven – can benefit from what is called ‘early intervention’ or ‘early support’.

Early intervention or support combines therapy practices and supports that help children to develop early skills that can provide the child opportunities to live the life they want. Early intervention support is often provided through play-based therapy, as play is often the most effective way for a child to learn, in conjunction with educational support for the child’s support network including their parents, teachers and peers.

While support can be beneficial at any age, early intervention or support can be important because new skills are much easier to learn when you’re very young.

That’s because there are key developmental stages that our brains go through in early childhood and tapping into these stages can make it easier to learn new things.

Think of how children pick up a second language or learn to play a musical instrument much more easily than an adult trying it for the first time. This ability to learn is related to what scientists call brain plasticity, which really just means how easily the brain develops.

We never lose ‘brain plasticity’ though, so if your child isn’t diagnosed until later in life, support and services can still form an important and necessary part of your child’s development and can have a positive impact on their life at any stage.

And while more research is required on the long-term benefits, initial studies suggest that early intervention or support can lead to more independent and functional communication, independence with daily living skills, and can build a range of other skills that can support quality of life.

What is early support?

Our ability to focus, absorb information, communicate and socialise has a direct impact on our quality of life. If we can focus, we can learn new things more easily. If we can communicate, we can not only express our needs but also form connections with people. If we can socialise, we can build meaningful relationships.

For autistics some or all of these skills can look different, which can make it challenging for others to understand and support children to have their needs met. Early support is designed to develop skills in these, and other areas, so that children develop essential skills early in life.

Early support generally focuses on understanding the child’s individual social and communication skills, along with behavioural and cognitive skills and supporting the development of these areas. This includes things like supporting the child’s ability to focus and attend so it is easier to learn, building language skills in order to communicate functionally and understand language, as well as developing daily living skills.

Early support brings together different therapies, that can assist your child, and are tailored to their unique strengths and challenges.

Early support might be offered by one professional, or may bring together several professionals, either through a service provider, organisation, private or government practice. Some programs can be delivered one on one, in small groups, at home, in a centre, or in the community.

Be sure to engage a professional who is well-trained in the therapy they are providing, and who also sees and responds to your child, and your family’s needs.

How do you choose the right services for your child?

As everyone’s experience of autism is unique, there is no one-size-fits-all service. Knowing your child’s strengths and needs will assist you in finding the right supports and services for them.

There are a wide variety of therapies, strategies and programs available, some backed by scientific studies and others built on anecdotal evidence.

That means you’ve got to do your research to find out what is best for your child.

It seems that for success in science or art, a dash of autism is essential.

We encourage you to look into the programs and strategies you are considering to see how well researched they are.

Here is a comprehensive guide to analysing the Scientific Evidence for strategies and interventions.

It is also good to talk to accredited professionals about how they are evaluated.

Don’t be afraid to ask questions of the people who are providing support and therapy to you and your family to be certain they are right for your child. Ask for more than anecdotal evidence – that is, more evidence of their effectiveness than personal testimonials, such as research articles.

There is a need for greater research into therapy programs for autistic people to fully evaluate their effectiveness, but some are better researched than others and recommended by professionals.

Beware of any programs that make overly optimistic claims about the results they can achieve. Unfortunately, not all therapy approaches and programs are supportive, and some are based on outdated ideas of autism being something that should be fixed, or are built on ideas about the causes of autism that simply aren’t true. In worst case scenarios, some can be harmful to your child

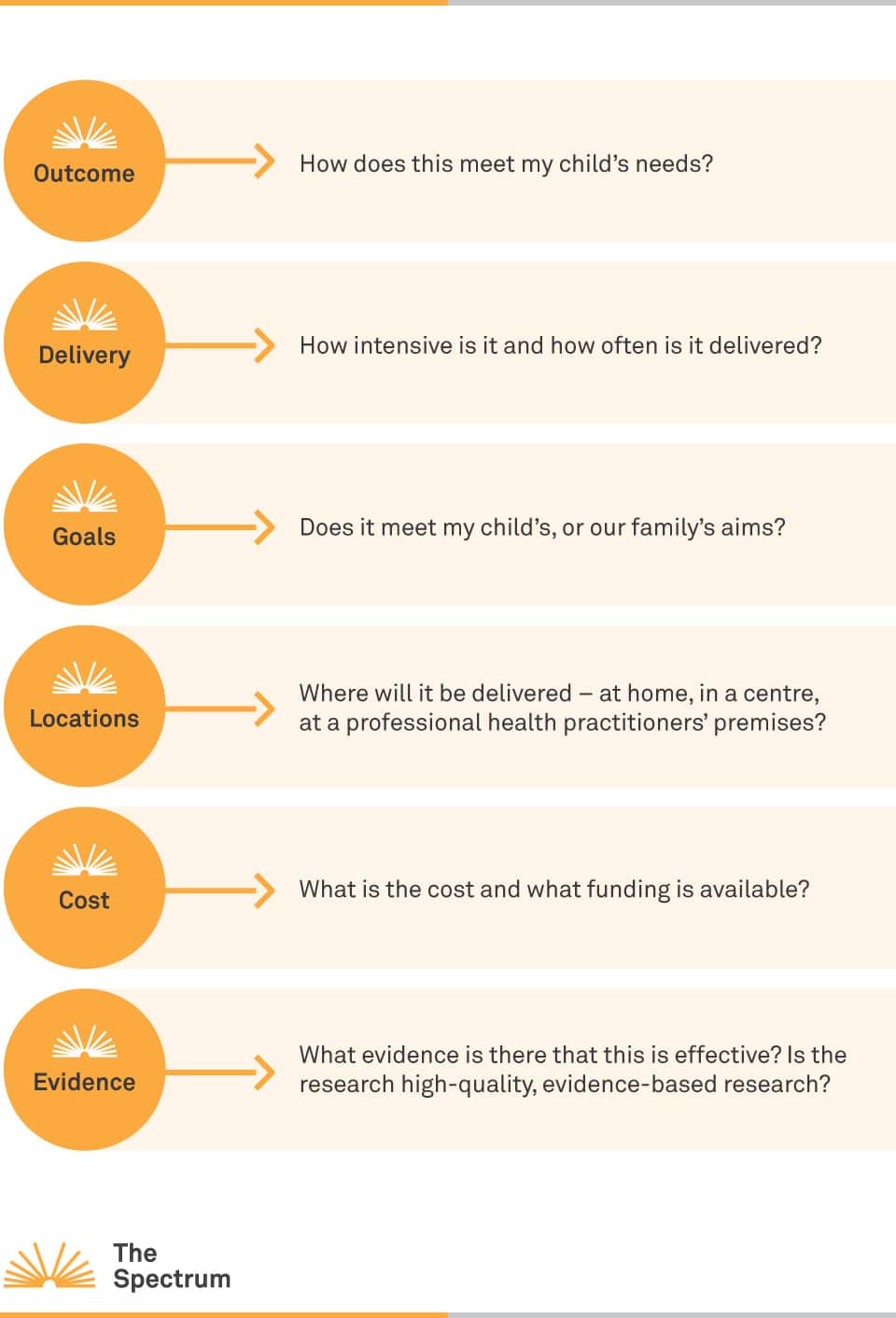

The Early Intervention for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: ‘Guidelines for Good Practice’ 2012 lists these questions when considering whether a program or therapy approach is for them:

- What are the specific aims of the program?

- Are there any medical or physical risks?

- What assessments of individual children are carried out prior to the intervention?

- What is the evidence base for this intervention?

- What evaluation methods have been used to assess the outcome of intervention?

- Do the proponents of the treatment program have a financial stake in its adoption?

- What is known about the long-term effects of this treatment?

- How much does it cost?

- How much time will be involved?

Essential, we need to ask our selves; ‘Am I doing the right thing in the right way with the right person at the right time in the right place for the right result – and am I the right person to be doing it? … and, is it at the right cost?’ (Cusick, 2001, p. 103).

Services that have been evaluated by the Department of Social Services can be found here. Or visit our Support and Services page for further information about services and supports in your community, specific to autism.

You can also check if a provider is registered with their professional association or the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency website.

The National Disability Insurance Scheme covers early intervention for children 0-6 years. If you are under the NDIS, you can find recommended providers on the website here. Or visit our Financial support page.

What makes early support effective?

In 2020, the Autism CRC produced the Interventions for children on the autism spectrum: A synthesis of research evidence.

The report outlines the core principles that are important to interventions for children on the autism spectrum:

– Holistic assessment – an initial assessment of an individual’s strengths, goals, challenges and preferences

– Individual and family-centred – the child should be placed at the centre of clinical management with the aim to understand and build the capacity of the individual and family to meet a person’s unique needs

– Lifespan perspective – a perspective that acknowledges that people grow and change throughout their lives as they are faced with new tasks, challenges and opportunities, and that capacity around a person will also change over time

– Evidence-based – interventions are most effective and safe when they are based on the best available scientific evidence

Applying an early support can involve everyone assisting your child, including family members, therapists, any childcare providers and/or teachers.

The support should outline your child’s strengths and needs, set goals for the support (agreed by you and your family and those involved) and outline how these goals will be monitored and achieved. Once a support is in place, it should be reviewed every six months to make sure it is continuing to meet your child’s needs.

One of the most important things is that you and your child feel comfortable with the person, or people, you’re working with.

Children respond more to people they feel safe with and are more likely to learn in a comfortable environment.

What types of supports are there?

An intervention is the word used to describe any therapy or service that is used to help support an autistic person’s quality of life.

These generally fall into one of the following categories:

Behavioural interventions

As the name suggests, these types of interventions focus on behaviour – understanding it, and then teaching new behavior, that is more beneficial to you or your child.

They teach new behaviours and skills, usually around simple everyday tasks, using structured techniques and gradual progress.

Behavioural interventions are among the most commonly used, so they are likely to be better researched than other types, though you should always look at what evidence-based research is available.

When talking about behavioural interventions, you might hear the term Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA).

ABA is a range of techniques and/or strategies that are used in some behavioural therapies.

Generally, they involve identifying a behaviour or skill, setting a goal towards it and breaking it into tiny steps to teach in a highly structured way.

This might target a specific behaviour, such as washing their hands or saying a particular word. Or it might look at a broader area of self-development, such as improving overall communication abilities.

Progress is measured throughout so that changes can be made to suit the child’s needs.

Developmental interventions

Rather than being focused on outward behaviour, developmental interventions look at what skills a person needs to develop to assist with daily life and enhance their ability to form meaningful relationships with others.

This focus is often on emotional and social skills. For example, facial expressions and gestures might be exaggerated to help people on the spectrum, specifically children, associate them with the emotion and learn to ‘read’ people’s emotional responses.

Generally, these therapies are child led, in that the therapist reacts to the child rather than the other way around. Playful techniques are used to encourage interactions and any response from the child is treated as meaningful.

Over time, therapists build engagement with the child, encouraging more interaction. Once a relationship is established, specific skills can begin to be taught.

These types of interventions also often use settings that are part of everyday life but in a safe and structured way that makes the child feel safe enough to learn skills.

Combined interventions

Some therapies combine elements from both the behavioural and developmental therapies, or aspects of other types of interventions.

These can be highly effective as they bring together the relevant parts of different styles of interventions, depending on the therapies they are combining.

Therapy-based interventions

Any single therapy that targets one particular aspect of a person’s development is classified as a therapy-based intervention.

An example of this is speech therapy for building communication skills or occupational therapy for developing physical movement. This can also include Art or Music Therapy.

Therapy-based approaches are often combined with other interventions.

Family-based interventions

As the intensity of therapies – that is, how many hours are spent on them in different environments – can have an impact on their effectiveness, family involvement is a powerful tool.

Family-based interventions put family at the core of any therapies and are built around strong, collaborative relationships between the family and professionals. They often include providing training, support, guidance and information for family members to be able to work with a family member or child on the spectrum.

Medical interventions

Medical interventions are generally prescribed for problems or underlying conditions associated with, but not necessarily caused, by autism, these are considered to be co-occurring conditions.

It’s very important that any medical intervention is prescribed by and managed by your doctor or health professional. What works for one person may not work for all, and all medications can have harmful side effects. For some medications, the long-term effects are unknown.

Just like therapists, medical practitioners have different skill sets and practice areas of interest. It can be helpful to find a medical provider who has a clinical interest or understanding in supporting autistic people. If you are not sure, you can always ask the provider or medial practice.

Alternative interventions

Therapies that are generally are not widely accepted as part of conventional Western medicine or that aren’t supported by scientific evidence are classified as alternative interventions.

While alternative therapies have become more popular in recent decades, they should be considered with caution, especially in relation to autism. Some alternative therapies – especially those that make wild promises or ridiculous claims to ‘cure’ autism – may do serious harm.

As with any intervention, don’t rely on personal stories or let promises that sound too good be true sway your judgement. Always ask questions and do your research to see whether the therapy will benefit you, or your child.

Evidence-informed strategies and interventions

There are a range of strategies and interventions that can be used to develop skills and to support the needs of people on the autism spectrum.

These include:

- Evidence Informed Practices: designed to address a single skill or goal of a people on the autism spectrum.

- Evidence Informed Interventions and Programs: consisting of a set of practices designed to achieve a broad learning or developmental impact on the core characteristics of autism.

Generally, these programs are characterised by:

- Organisation: around a conceptual framework)

- Operationalisation: manualised procedures

- Intensity: a substantial number of hours per week

- Longevity: occur across one or more years

- Breadth of outcome focus: multiple outcomes such as communication, behaviour, social competence targeted.

The different types of evidence-based interventions currently include:

- Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA)

- Early Start Denver Model (ESDM)

- DIR/Floortime Approach*

- Developmental Social-Pragmatic (DSP) model

- RDI – Relationships Development Intervention

- Speech Generating Devices (SGD) and other Augmentative & Alternative Communication (AAC)

- PECS – Picture Exchange Communication System

- Ayers Sensory Integration (ASI)

More can be found visiting the Autism CRC Interventions for children on the autism spectrum: A synthesis of research evidence.